- Home

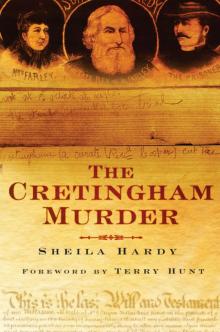

- Sheila Hardy

The Cretingham Murder

The Cretingham Murder Read online

THE

CRETINGHAM

MURDER

THE

CRETINGHAM

MURDER

SHEILA HARDY

Dedicated to Diana and Henry Mann

whose love of the past and curiosity to

know more led to this investigation.

First published 1998

This edition published 2008

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Sheila Hardy, 2008, 2013

The right of Sheila Hardy to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5259 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Terry Hunt

Introduction

1. Background to the Case

2. Sunday 2 October 1887

3. The Aftermath

4. Monday 3 October 1887

5. Thursday 6 October 1887

6. Friday–Sunday 7–9 October 1887

7. The Assizes, 15 November 1887

8. Finale

Appendix: Members of the Inquest Jury

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to express my sincere thanks to the many people who have helped me build up the background to this case: Vic Llewellyn of The New Bell, Cretingham; the late Mrs Phyllis Burman; Mrs C. Ransome; Michael Brown; Alan Lettin; Neil Langridge; Mrs Wilda Woodland; A.A. Lovejoy; Beryl and Peter Smith; Julie Ashwell; Sarah Mitchell; Helen Vallier; Brenda Tracey; Rae Atkins (NZ); Michael Pinner; Peter Mays; Ann Hoole, Librarian of Framlingham College; Brian Martin, Magdalen College School; Robert Leon, archivist, St Luke’s Hospital; Rita Read, Haringey Museum & Archive Service, for details of Northumberland House;the helpful staff of the County Record Offices of Berkshire, Dorset, Gloucestershire, Kent, Norfolk, Suffolk, Surrey and Wiltshire; Ilfracombe Museum; Portsmouth City Record Office; the PRO at Kew and the British Library newspapers.

And an extra special thank you to Mike Reynolds and Patricia Burnham who ‘dug deep’ into records on my behalf; Trish not only entered into my enthusiasm to find the elusive Harriet Louisa but has kept the search going.

FOREWORD

I grew up in the village of Cretingham in the 1960s. Throughout my childhood, I heard older villagers talking about the terrible murder of the vicar which had happened so many years before. I believed the tales (fanciful or not?) that his spilled blood still stained the wooden floorboards of the bedroom at Cretingham House, where the awful deed had taken place. With each telling, the story became more and more grisly – not that my youthful imagination needed much prompting to run riot!

In 1998, I was honoured to be asked to write the foreword for Sheila Hardy’s original, limited edition of The Cretingham Murder. I am delighted to reprise my thoughts for this updated version, which will deservedly be reaching a wider audience.

For the past decade I have been privileged to have the role of Editor of the East Anglian Daily Times newspaper. There is, of course, a strong link between the newspaper and the murder which took place in Cretingham in 1887. This sensational occurrence was one of the newspaper’s biggest early stories and was reported in full, graphic detail in the days following the heinous crime. Far more detail than we would be allowed to use, or indeed would want to use, in these modern times!

This is indeed a dramatic tale in which the truth is every bit as compelling as the myths and legends which I heard during my childhood, and this time no youthful fantasies are required.

Terry Hunt

Editor, East Anglian Daily Times

INTRODUCTION

In the late summer of 1887 carpenters Frank Dodd and William Woolnough were among the craftsmen putting the finishing touches to a hunting lodge of mansion-like proportions, close to the upper reaches of the river Alde in Suffolk.

William lived in the nearby village of Friston where Frank, who was an Essex man, had found lodgings – and a young woman called Elizabeth Ellen Gildersleeves – for the duration of his contract. As they worked sawing planks for floorboards, or hammering into place the pieces of good seasoned oak which would cover the tops of the columns that rose high from the ground floor to support the massive arched glass dome stretched above the first floor gallery, the thick leaded pencil, an essential tool of their trade, was never far from hand. Used mainly for marking where incisions should be made, they occasionally used it to leave messages, not just for each other but for those who would come after them. It takes very little imagination to reconstruct what led one of them to write on a handy plank, somewhat piously, ‘our poor heads wont ache when this is taken down. This ought to be a good warning to young men to keep away from the beer.’ Thick head or not, the handwriting is both steady and remarkably good, a testimony to the solid basic education of the period.

The men seem to have been very conscious of the fact that what they were building would be there long after they were dead and buried, for in another inscription they direct future craftsmen working on the lodge to seek them ‘among the moles’. The desire to leave one’s name for posterity appears to loom large among the company, for George Rackham of Snape and Bob James from Leiston both added their signatures to pieces of wood which would be hidden from contemporary eyes.

Not all the writings were of sombre aspect. Inspired on one occasion to break into rhyme, the verse they produced is far too lewd to be incorporated here! Pride in their work is contained in the words ‘This cornice was fixed October 8th 1887 by Frank Dodd of Chelmsford Essex and William Woolnough of Friston Suffolk.’

8 October was a Saturday and the two had had much to talk over during that week: news so gruesome that one of them had written the important message which was to provide the inspiration for this book.

Just over a hundred years later, in the late summer of 1996, Henry Mann, a carpenter from Peasenhall, was engaged in carrying out renovations to that isolated hunting lodge. Taking out the old boards, he suddenly found himself reading the words left by his long dead predecessors. Being the sensitive craftsman he is, he found himself forming a bond with them, unable simply to jettison these messages from the past into the waiting skip. One piece in particular caught his imagination. Written along the edge of a board were the words ‘A fearful murder’. Tantalizingly, a second board carried the same three words and no more, as if lack of space had led to the abandonment of the project. Undaunted, Henry scrutinized every board until at last he found the one which read ‘A fearful murder was committed the first day of this month (October 1887) at Cretingham.A curate (Revd Cooper) cut the vicar’s throat at 12 o’clock at night. He stands committed for trial.’

Coming from Peasenhall where even today every villager knows the story of the murder of Rose Harsent, just as every Suffolk resident has heard of Maria Marten’s murder in the Red Barn, Henry wondered why he had never come across an account of this ‘fearful’ murder. Following his discovery, Henry and his wife, Diana, came to a talk I gave in Saxmundham. Thei

r simple question – could I verify the statement on a piece of wood – started me off on a long, fascinating, and at times frustratingly infuriating quest to find the background to and perhaps the truth of a little known but quite bizarre Suffolk story.

1

BACKGROUND TO THE

CASE

The Revd Farley

When the Revd Mr William Meymott Farley was appointed to the living of Cretingham in 1863, there was no house available in the village considered suitable for a gentleman and his family. So, with the aid of a mortgage of £300 from Queen Anne’s Bounty, a clerical building fund, plans were promptly put into place to build a new parsonage. We have come to expect to find the large Victorian village vicarage situated close to the church it served but as this was not feasible in Cretingham, the new house was set in pleasant surroundings on the approach to the village on the Otley road. Until the house was ready, the Farleys lived in the nearby village of Brandeston, the vicar commuting to attend his parishioners.

In his late forties, Farley had been a clergyman for twenty-three years, having trained at St Bee’s, a theological college noted for its advancement of the Evangelical cause in the Church of England. In entering the Church he was following a family tradition, his father having held the perpetual curacy of Broad Town in Wiltshire.

The vicarage at Cretingham, from a painting by Frederick Farley, 1875. (Author’s collection)

The young man, having served his apprenticeship acting as curate in two parishes in Lancashire, was given better paid employment at Baldock in Hertfordshire in 1841, which had enabled him to embark on marriage the previous year and later, the responsibilities of fatherhood. His firstborn, a son called Frederick, marks this period in his father’s career by bearing Baldock as his second name. A curacy in Saffron Walden provided extra income but by 1845 William had been appointed to the living of Haddenham in Buckinghamshire and another son, Thomas and a daughter, Ada were added to the family.

In 1848 Mrs Farley died. The following year, William married Miss Susannah May who was to provide him with two further sons, William and Arthur and two daughters, Susannah and Elizabeth.

Twelve years in Haddenham were followed by five in Kent and it was from the parishes of Bexley and Erith that William was to make his final move to Cretingham.

By the time the family moved into the new parsonage with its ‘favourable southerly aspect’, the family was growing up. Frederick at 21 had already left home. Described in the 1861 census as a ‘chymist’ he later became a ship’s surgeon. Thomas was 15, William 13, Susannah 11, Elizabeth 10 and Arthur 7. The 12-year-old Ada had died in 1860.

Curiosity makes us ponder on what life was like for the family in those early days. Since the later census records no living-in staff, we can only assume that the domestic staff came daily from the village. There would surely have been at least two maids as there had been in their Bexley household, with a gardener to attend to the extensive grounds and also act as groom when carriage transport was required.

And what of the education of the children? William, it has been established, spent the years 1865–6 at what is now known as Framlingham College. Arthur was probably taught at home with the girls until such time as he went off to school. Maybe they employed a daily governess and possibly both parents helped with the children’s education.

Such speculation is beyond this present narration. All we do know is that the Revd Farley performed his parochial duties according to the evangelical precepts held by most of his fellow clergy in Suffolk at that time. That he felt strongly about his own faith and the need to inspire higher and more moral principles into that faith is witnessed by his one known published work on the subject, a tract entitled On Regeneration. Sadly, I have been unable to trace a copy of this work. His memorial tablet in Cretingham church states that he was a Greek scholar. Possibly, like many clergymen of the period, he had set himself the task of translating or commentating upon the great classical works.

During his early years at Cretingham, he was also very involved in politics, actively campaigning locally for the Liberal Party. However, in 1868 he severed all connection with that party when Gladstone introduced the measure to disestablish the Protestant Church of Ireland. No doubt, like so many of his colleagues, he saw this as a dangerous move which would encourage the spread of Roman Catholicism in England. A stalwart member of the Church of England, Farley was essentially a Protestant and as such, he was willing to befriend those who took their faith from within the Non-Conformist churches. A brief glimpse of Farley as outsiders saw him came in this tribute by Samuel Pendred, the Minister of the Union Chapel in Aldeburgh:

The good vicar of Cretingham...had been a visitor at Aldeburgh (1886) and when here, occupied lodgings where his gentle disposition was noticed and felt; he also manifested the goodness and charitableness of his Christian character by worshipping on several occasions with nonconformists. It was not only the pleasant surprise of seeing a clergyman in our dissenters place of worship that has made his visit remembered but his warm grasp as he took me by the hand when service was over, his fatherly, ‘God Bless you’ and earnest words about ‘the one way to that home where we all shall meet as brothers.’ . . . I have some hymns of his own composition sent from Cretingham among them, ‘His love shall keep me every hour/And raise me to the sky.’

Physically, Farley was a very large man, his weight increasing further as he aged. A newspaper report recalls that ‘his well known portly figure was often seen in the streets of Framlingham’. It was rumoured that at the time of his death he weighed nearly twenty stones. In old age he sprouted a long, bushy white beard which gave him a truly venerable appearance.

In later life his par ishioners found him of somewhat irascible temperament, given to impetuous outbursts over minor matters or indeed over nothing at all. With true Suffolk forbearance they ‘never took much notice of it’. One gains the impression too that he could be of a jealous disposition and was likely to be mean where money was concerned. Certainly he was reluctant to pay his curates their due. It may be that at some stage he had financial problems, as there is evidence that he had found it necessary to borrow £100 from the Trust Fund set up for his son, Thomas by his maternal grandmother.

Not an easy man to live with it would seem, though perhaps the situation was not helped by the long illness suffered by his wife, Susannah, nor the tragedy which struck the family just before her death.

In early 1880, their son, William brought his wife, Ellen, their 12-year-old daughter and new baby son of 2 months for a visit. On 19 January, the baby had a slight cold but not enough to prevent it being taken out for an airing. At five o’clock the following morning, Ellen fed the child and returned it to its cot but when the nursemaid went into him at eight, the baby was dead. A coroner’s inquest was held at the house – foreshadowing the similar event which would occur seven years later. The tiny corpse was laid to rest in a corner of Cretingham churchyard, close to where Mrs Farley would join him in March the next year.

At her mother’s death, only Elizabeth was still living at home. Frederick had by then qualified as a surgeon and was serving on board a ship. Thomas had followed his father into the Church, William was a hydraulic engineer’s clerk and Arthur eventually became an attendant in an asylum. Daughter Susannah had been married at Cretingham church in 1878 to Mr Gilbert Palmer, the son of a London wine merchant. The young people made their home at the Black Bull Inn in the Old Kent Road, London.

Then 28, Elizabeth had no plans to remain at home as the dedicated spinster daughter of a clergyman. Not for her the role of housekeeper of her father’s establishment, shouldering the attendant parochial duties of sick visiting and Sunday schools. Six months after her mother’s death, in September 1881, she was married in Portsea, Portsmouth to Archibald Court, a naval officer aged 34, who carried the rank of paymaster on board HMS Wellington. Court has the rare distinction of appearing twice on the census records for 1881. He is listed with the complement of his the

n ship, HMS Duke and also at private lodgings at 45 St Thomas Street, Portsmouth.

Elizabeth’s brother, Arthur acted as a witness to the marriage but we can only surmise that the Revd Farley travelled to Hampshire for the celebrations. For now, a strange coincidence occurred. From those same census records mentioned earlier we learn that also living in Portsea at that time as a boarder at 6 Gordon Terrace was (Harriet) Louisa, the 40-year-old widow of Lt-Col William Moule. Where the pair met, who introduced them, we shall probably never know but on 9 November the Revd Farley had his third wife.

They were married at St James’s church, Clapton, in the London district of Hackney. One of those who signed the marriage register as a witness was Farley’s other son-in-law, Gilbert Palmer. Thus we may conclude that the match had family approval. Although the marriage was by licence rather than Banns, Louisa gave her place of residence as Clapton – perhaps she had moved into lodgings for the statutory period. Two of the other witnesses offer a clue to the intricacies of this affair. One, Charles Atkins, a shipping agent, was a middle-aged widower who had also recently remarried. His bride, a widow, was another Louisa, and she had been born Louisa Farley. Coincidence? Or was she the Revd Farley’s niece? And was it in her home that the bride-to-be, Louisa Moule, stayed in the weeks before the wedding?

Harriet Louisa

What sort of woman did the vicar bring back to Cretingham? Described as still being in her prime, she was lively and extroverted, used to the gregarious life of the wife of an army officer. So how did she take to the quiet rural life and what were the villagers to make of her?

The old Suffolk saying ‘Tha’s a mystery’ just about sums her up. Research has shown that her early life is indeed shrouded in mystery. If, as she stated for the census return of 1881, she was 40, then she was born around 1840. She gives Windsor as her place of birth and on her marriage certificates her father is named as Robert Head, a grocer. So far no record of either her birth or details of her parents have been found.

The Cretingham Murder

The Cretingham Murder