- Home

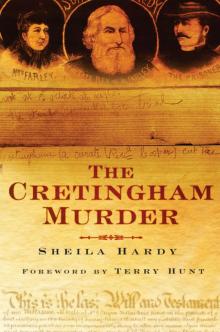

- Sheila Hardy

The Cretingham Murder Page 5

The Cretingham Murder Read online

Page 5

‘But,’ Mr Martin, the magistrates’ clerk responded, ‘We understand that he is dead and you are charged with the murder.’ ‘I don’t think he is,’ Arthur persisted.

John Martin gave up and reminded Arthur that the best advice had already been given to him, namely to say nothing until the next hearing. That was then set for 11 a.m. on the coming Thursday.

In Cretingham they were preparing for the inquest. Before the formal proceedings were opened at The Bell Inn, at that time situated opposite the church, those who were to form the jury were summoned to the village clubroom which stood in the vicarage grounds. Here twenty-two men from the surrounding area were sworn in (see Appendix for list). Samuel Stearn, a small farmer and pig-breeder from Brandeston, was elected to act as their foreman. The all-male jury was a mixed group, mainly farmers with a sprinkling of craftsmen; blacksmith, builder, wheelwright, miller and an innkeeper. Most were of middle age. It was unfortunate that two pairs had the same surname and since forenames or initials did not always appear in the press reports, there is, for example, no way of knowing when we come to the inquest, which Mr Juby it was who adopted the aggressive line of questioning.

The presiding coroner was Mr Cooper Charles Brooke whose first task was to lead the jury into the vicarage to view the scene of the crime. In the vicar’s bedroom the ‘horrible gash in the victim’s throat was exposed’. (Something that has puzzled me was Farley’s full beard. Two photographs show it to be long enough to touch his collar bone. It was never made clear if it had been trimmed before his death. If it had not and if Farley had been lying on his pillow at the time of the murder, how had Arthur been able to find his victim’s neck with such accuracy?)

The bloodstains on the carpet which showed the position in which Mrs Farley had found the body were also inspected closely. The jury noted too the padlock which fastened the intercommunicating door before moving on to look at the curate’s room. This too, had been left untouched, so they were able to see for themselves the rumpled bed which suggested that Arthur had been tossing from side to side.

Having completed their examination of the premises, the coroner and jury moved on to The Bell Inn where Major Heigham, the Chief Constable, the witnesses and the gentlemen of the Press and as many others as could squeeze in had already assembled.

One can imagine the hush when Arthur was brought in by Supt Balls and Sgt Bragg. He was still wearing his clerical garb topped by a thick overcoat and a round soft hat. He failed to remove his hat and one of the police officers took it off for him. We are told that he was given a seat among (beside?) the jury. Although at first he seemed somewhat bemused by it all, after a while he appeared to be taking an intelligent interest in the proceedings.

The first witness was, naturally, the widow. Most of the newspaper accounts were to comment on how calmly Mrs Farley conducted herself but some were surprisingly critical of the widow. The Dorset County Chronicle primly stated, ‘Mrs Farley is still in the prime of life . . . She was wonderfully calm and still wore coloured flowers in her bonnet.’ This was indeed an affront to the Victorian code of decorous behaviour. However, the Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette had worse: ‘. . . the wife of the deceased who was the principal witness, in the course of her evidence exhibited extraordinary levity.’

No doubt, given the horror of the circumstances in which she had been embroiled, the spectators had expected a display of heart-rending emotion from the grieving widow. That they were disappointed may have been the result of Harriet Louisa still being in a state of shock. Another possible explanation is that her years spent with the army had taught her rigid self-control.

Had she presented a more pathetic picture, it is possible she would not have been subjected to the rigorous questioning that followed her initial statement of events. As the inquest progressed, so it became clear that not only was she not particularly liked by the local people, but she had in fact been the subject of gossip among them.

Having detailed the events leading up to her going to bed, she was asked about the rap at the door. This, she said, she had not heard herself, yet in the previous account she was reported as saying she had heard what she thought was the maid rattling the candlestick.

The next discrepancy came in her account of what happened when Arthur reached the side of the bed where the vicar was lying. She now said that it was Arthur who had twice said ‘What do you mean?’ The coroner picked her up on that, asking, ‘Mr Farley said so?’ On the contrary, she replied that it was definitely Arthur who had said it and her husband who had laughed. Mr Farley had laughed in his usual bright way as if not sick, as much as to say ‘Don’t be foolish’ or something like that.

The Suffolk Times and Mercury report continued:

Coroner: He said to the prisoner ‘Don’t be foolish?’

Mrs Farley: No, he didn’t say it, but it was in that kind of way. The vicar made no remark. He only laughed. He saw Mr Cooper was wrong and tried to intimidate him and send him away. When Mr Cooper made the remark, ‘What do you mean?’ I knew there was something wrong, and I went to him and ordered him out of the room. I said to him, ‘What do you mean talking like that? Get out of the room,’ and sent him out and followed him out.

Coroner: What took place then?

Mrs Farley: I did not close the door.

Coroner: Did you observe any blood flowing?

Mrs Farley: My husband said, ‘Oh Louie, he has’– done so and so.

Coroner: The deceased said his throat was cut, didn’t he?

[The witness nodded her head]

Coroner: Was that when Mr Cooper was in the bedroom?

Mrs Farley: I should say it was when he was passing out. He was most likely on my side of the bed, near the door. I went round immediately to my husband, and said, ‘Nonsense, nonsense, you fancy things’.

Coroner: Did you see blood flowing then?

Mrs Farley: No, I did not. I didn’t believe it; didn’t believe it was true.

Coroner: How long was it before you saw blood?

Mrs Farley: I followed Mr Cooper to his room, fearing that he had something in his hand. My first thoughts were that he would go to the servants.

Coroner: Did you go to the prisoner’s room?

Mrs Farley: Yes.

Coroner: Was he there?

Mrs Farley: Yes.

Coroner: Did he make any observation to you?

Mrs Farley: No.

Coroner: Did you see him put a razor or anything of that kind down?

Mrs Farley: No; he was standing quite upright in his room. He said nothing. I asked him what he had in his hands, and he said ‘I have got nothing.’ I tried to intimidate him, but he held out his hands and said ‘I have got nothing.’

Coroner: Were his hands open?

Mrs Farley: Yes.

Coroner: Both of them?

Mrs Farley: Yes.

Coroner: How long did you stay with him?

Mrs Farley: Not a second. I ran across the room and took his razor case off the dressing-table. He didn’t seem to notice that I took it but I did. I threw it into another room, and then ran back to my husband.

Coroner: You didn’t know whether the razors were in it or not?

Mrs Farley: No. I did not. My only thought was that he might make use of them.

Coroner: On your return to the deceased did you see any blood?

Mrs Farley: My husband was on the floor.

Coroner: Did you observe any blood?

[The witness nodded]

Coroner: Did you see any wound?

[The witness shook her head]

Coroner: Did you notice where it was flowing from?

[Again the witness shook her head]

Coroner: Where was your husband lying?

Mrs Farley: At the foot of the bed.

Coroner: How long did he live after that?

Mrs Farley: I should think nearly ten minutes.

Coroner: There must have been a quantity of blood on the floor?

Mr

s Farley: An immense amount.

Coroner: Did you ever hear the prisoner say he would commit suicide?

Mrs Farley: No, never. He did not like us to know that anything was wrong.

Coroner: I suppose there had not been any misunderstanding between the prisoner and yourself?

Mrs Farley: No.

Coroner: You are sure he had nothing in his left hand when he came into the room?

Mrs Farley: I could not see anything. I saw him standing there, with a candle in his hand, looking fearfully white. It was a shock to me, and I said to Mr Farley,

‘Good gracious, the man is mad.’

For the moment, the coroner had come to the end of his questions so now it was the turn of the jury to ask about anything which was unclear to them. Samuel Stearn, the foreman, went back to the moment when Arthur had stood beside the vicar’s bed.

Foreman: Did you see the prisoner handle Mr Farley at all?

Mrs Farley: No.

Foreman: You were not looking at him all the time?

Mrs Farley: No, I was not. I should not have been surprised if he had sat down in a chair and said, ‘Oh dear, I can’t sleep.’

Foreman: You didn’t see him turn the clothes down?

Mrs Farley: No, I did not. The clothes did not seem disarranged. My husband was quite placid upon the pillow. I saw nothing at all on the clothes.

Foreman: What did he do after that? Did he leave the house?

Mrs Farley: I went to him again afterwards, because I could not get anyone to help. I tried to staunch the wound with a cold water towel and screamed for someone to help me. I said to Mr Cooper, ‘Come and help me; you don’t know what you have done.’

It is interesting to note that at this stage there was no mention of Harriet Louisa’s sending for Bilney. However, she seemed somewhat attached to the phrase ‘you don’t know what you have done’ for she reiterated it later in answer to the foreman’s question as to whether or not she had conversed with Arthur on his return.

Coroner: Did you see him [Cooper] when he returned in the morning?

Mrs Farley: I went up to his room after he came in, between five and six o’clock on Sunday morning.

Foreman: Did you have any conversation with him?

Mrs Farley: I said, ‘You don’t know what you have done.’ He looked at me, and I said, ‘Shall I write to your mother?’ He said, Oh no.’ He was very boyish in some of his ways. He was only a boy.

Coroner: What do you mean?

Mrs Farley: Well, he is over 30 but I treated him quite as a lad. Sometimes I could look up to him for counsel and advice.

Then followed questions about Arthur’s poor appetite and inability to sleep and Harriet Louisa’s attempts to alleviate both conditions. The jurors, like the modern reader, found certain aspects of the events difficult to understand.

Mr Gocher: You say when you saw Mr Cooper at the door you immediately locked it again because you were afraid of him?

Mrs Farley: Yes; it was an unusual thing for Mr Cooper to come to my room at that time of night.

Mr Gocher: You had never seen him there before?

Mrs Farley: No.

Foreman: I wonder you opened the door a second time.

Mrs Farley: I should not have done so if Mr Farley had not told me to. I was not afraid of him, because I could always manage him.

Having answered the question asked, she went on to give further explanation:

Mrs Farley: I read to Mr Farley a great deal in the evening, and said ‘I will just step down and see how that poor man is’. Once or twice he looked at me, and I felt afraid, but I looked at him firmly, and thought to myself, ‘I’ll not be afraid of you.’

Examination of the witness was now taken up by Mr Juby whose somewhat aggressive manner suggests that he felt the widow was taking the whole business far too calmly:

Mr Juby: It has been reported that you asked Mr Cooper when he entered the room what he had got in his other hand?

Mrs Farley: I did not. I never said anything to him except, ‘Go away; what are you doing here?’

Mr Juby: Had you a light when he came in?

Mrs Farley: I could not tell. I have thought since that I must have lighted the candle before I went to the door, but I can’t remember.

Mr Juby: You were not burning a light?

Mrs Farley: No.

Mr Juby: Did Mr Cooper leave his candle in your room?

Mrs Farley: No; he took it away with him.

Mr Juby: Did he set down the candle before he entered into conflict with your husband?

Mrs Farley: Anyone would think so, but I did not see him.

Mr Juby: How was it you did not feel yourself called upon to keep in the room?

Mrs Farley: I was in the room.

Mr Juby: Then how was it you did not see him in conflict with your husband?

Mrs Farley: I did not notice him. I did not go round to that side.

Mr Juby: How was it you did not keep in the room?

Mrs Farley: I tell you I was in the room.

Mr Juby: If you were suspicious it seems rather anomalous that you should leave the room?

Mrs Farley: I didn’t leave the room.

Mr Juby: Then you saw him do it?

Mrs Farley: I didn’t see him. I heard him say, ‘What do you mean? What do you mean?’

Mr Juby: Was he holding the candle all the time he was by the bedside?

Mrs Farley: I don’t know; I did not notice particularly. Perhaps I was putting on my dressing-gown. I had nothing on but my night-gown.

Mr Juby: Did Mr Farley say anything to him when he attacked him?

Mrs Farley: He only laughed, as much as to say, ‘Don’t be foolish; I am not afraid of you.’

Mr Juby: Did the prisoner say when he came into the room, ‘I shall not hurt you?’

Mrs Farley: He said so to me. I said, ‘What do you want?’ and he said, ‘I shall not hurt you.’

Coroner: Didn’t you think it was rather a curious expression?

Mrs Farley: I didn’t think anything about it. I wanted to know what he wanted, and he said, ‘I shall not hurt you; I want to come in.’ I thought he meant he would not do any of us any mischief.

Mr Stearn, the jury foreman turned again to the strangeness of the curate coming to a lady’s room at that hour and then wanted to know if Mrs Farley had suspected for some time that he might be dangerous. This she failed to answer directly, saying instead, ‘We liked him very much, both Mr Farley and myself. We had always treated him like our own child. If he had been my own son or younger brother I could not have behaved differently.’

Printed words are incapable of the nuances of uttered speech so we cannot possibly know, though we may try to guess, if Harriet Louisa paused between ‘son’ and ‘younger brother’. In carefully building up the picture of the boyish curate was she trying to disguise the fact that she was far too young to have been his mother, there being only thirteen years between them?

It was at this point that Mr Juby, full of righteous pomposity, introduced into the case what was quite obviously the village gossip. In looking for a motive for the murder of the vicar, the locals were pretty sure that they knew what it was.

Mr Juby: I feel it is a very unpleasant position to occupy that I am now about to take, but, painful as it is, I feel it is my imperative duty, a duty I owe to myself having taken the oath, and a duty I owe to the public here assembled, to enquire into the cause of the death of your late husband, to ask these questions: Don’t you consider there was considerable animus in the mind of Mr Farley towards Mr Cooper?

Mrs Farley: Certainly not, not for sometime past. During the first nine or ten months there was some misunderstanding, but latterly he has been very different.

Mr Juby: Was there any reason for that?

Mrs Farley: Yes.

Mr Juby: Will you tell the Jury what it was?

Mrs Farley: There was some little unpleasantness about money matters.

This was not the a

nswer Juby was fishing for, so he came directly to the point: ‘I presume you know very well your character has been considerably aspersed.’

Imagine the gasp that must have run round the room and the knowing looks that were exchanged. The coroner quite rightly decreed that there was no need to go into that. If he thought he was defending the lady’s susceptibilities, he must have been taken aback by her reply. ‘I don’t mind about it. People will talk.’

The coroner directed Juby that he might ask the question if he thought it necessary. Harriet Louisa was quite happy to continue:

Mrs Farley: Mr Farley did not believe anything of the sort.

Mr Juby: I have a good deal to ask yet if you have the time.

Coroner: We have come here to enquire into the cause of death.

Mrs Farley: Ask any questions you please. I am quite willing to answer any questions.

Mr Juby: You say you had suspicions and took the razor case away?

Mrs Farley: I have had occasion to take my husband’s razor for the same thing.

Mr Juby: Have you ever seen Mr Farley strike Mr Cooper?

Mrs Farley: Never.

Mr Juby: Nor yet strike at him?

Mrs Farley: Mr Farley used to get little fits sometimes and get angry about nothing, but we never took much notice of it. He was an impetuous man.

Mr Juby: Of course you know that scandal and report have been very busy, and it is very natural that you should have the opportunity of explaining yourself.

Mrs Farley: Mr Farley did not believe all the little gossip.

Coroner: As I understand your reply it is this – that there has never been any impropriety between yourself and Mr Cooper.

Mrs Farley: (indignantly) Good gracious, certainly not.

Mr Juby: Did you ever go between Mr Cooper and Mr Farley?

Mrs Farley: I don’t know that I did.

The Cretingham Murder

The Cretingham Murder